Image 1 of 11

Image 1 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 11 of 11

Image 11 of 11

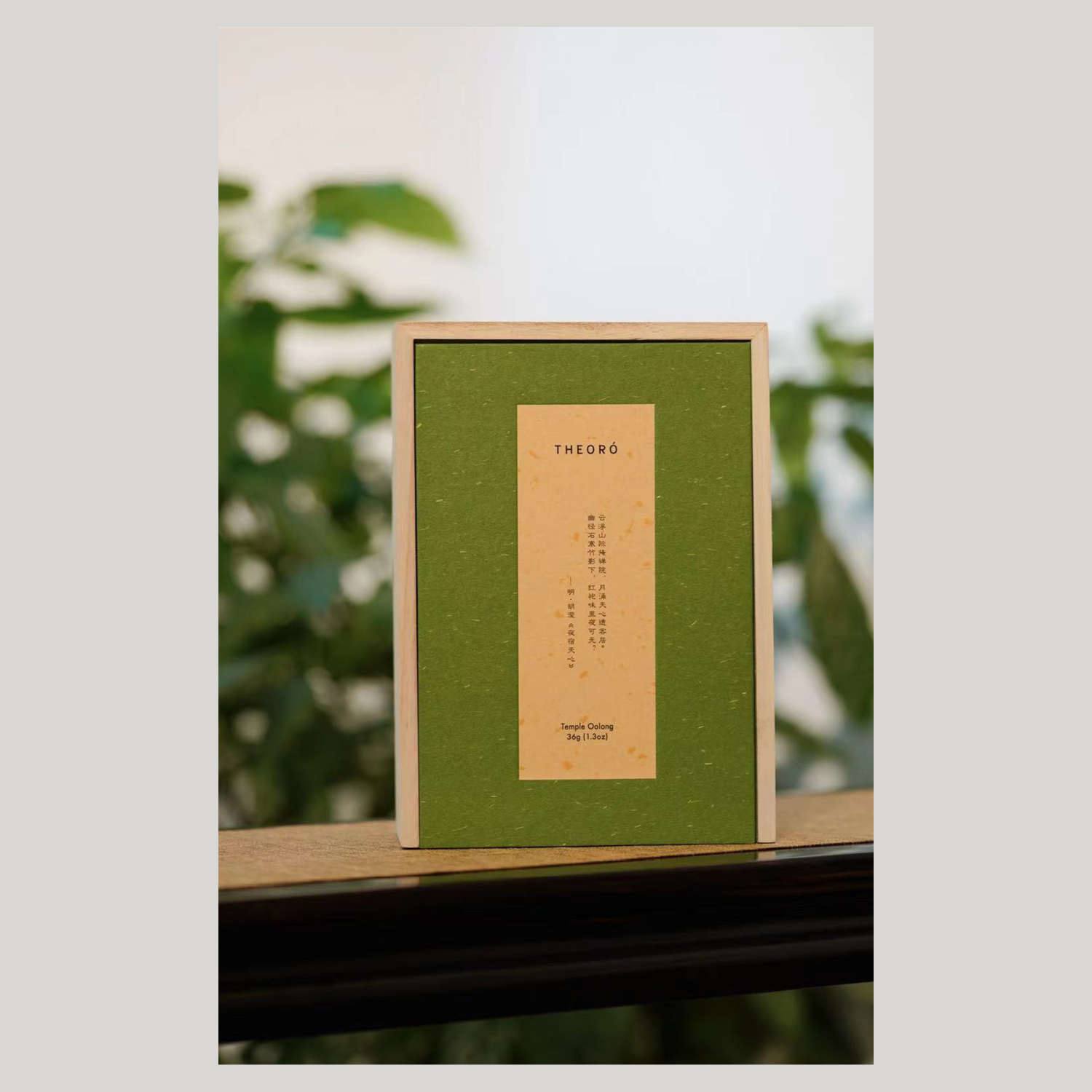

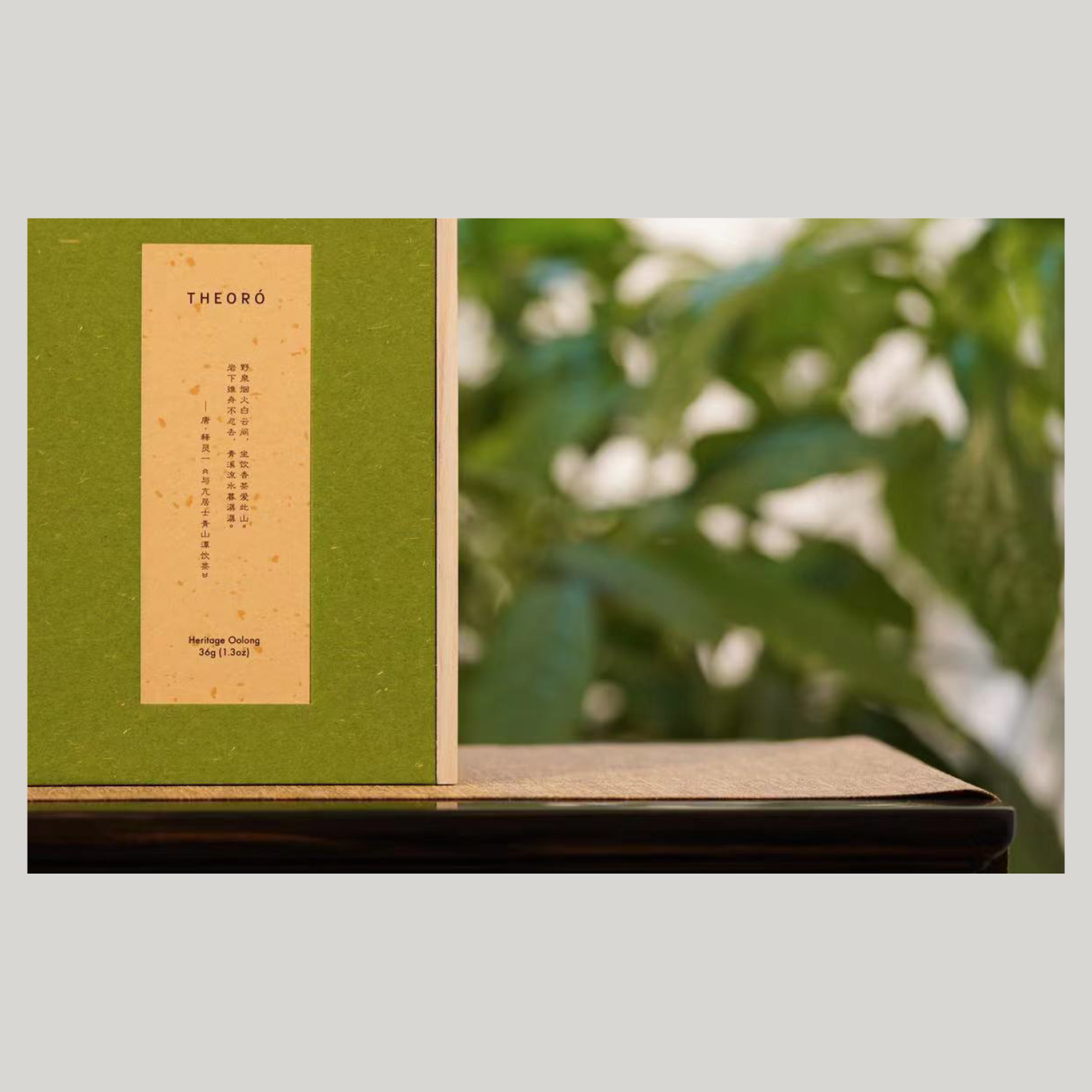

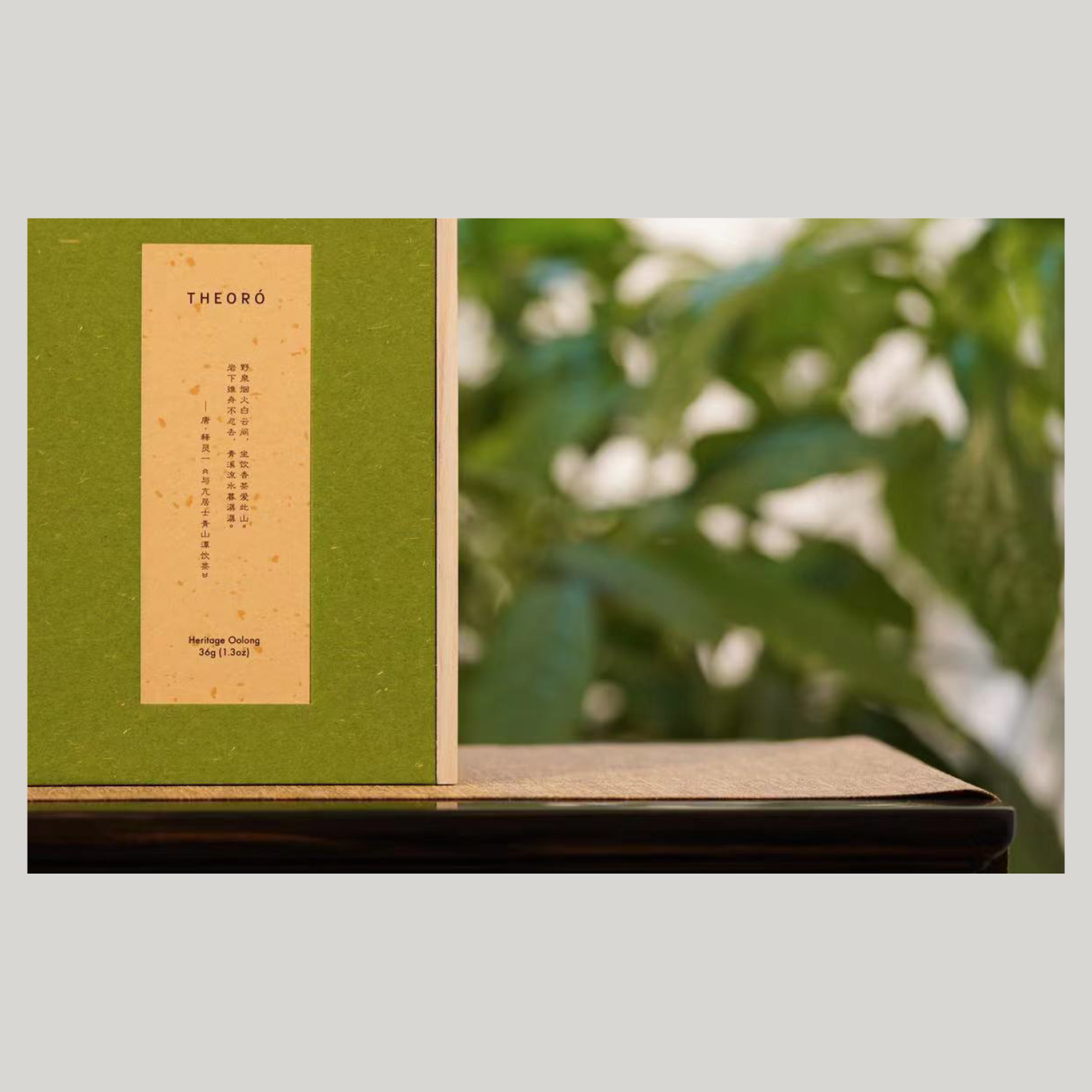

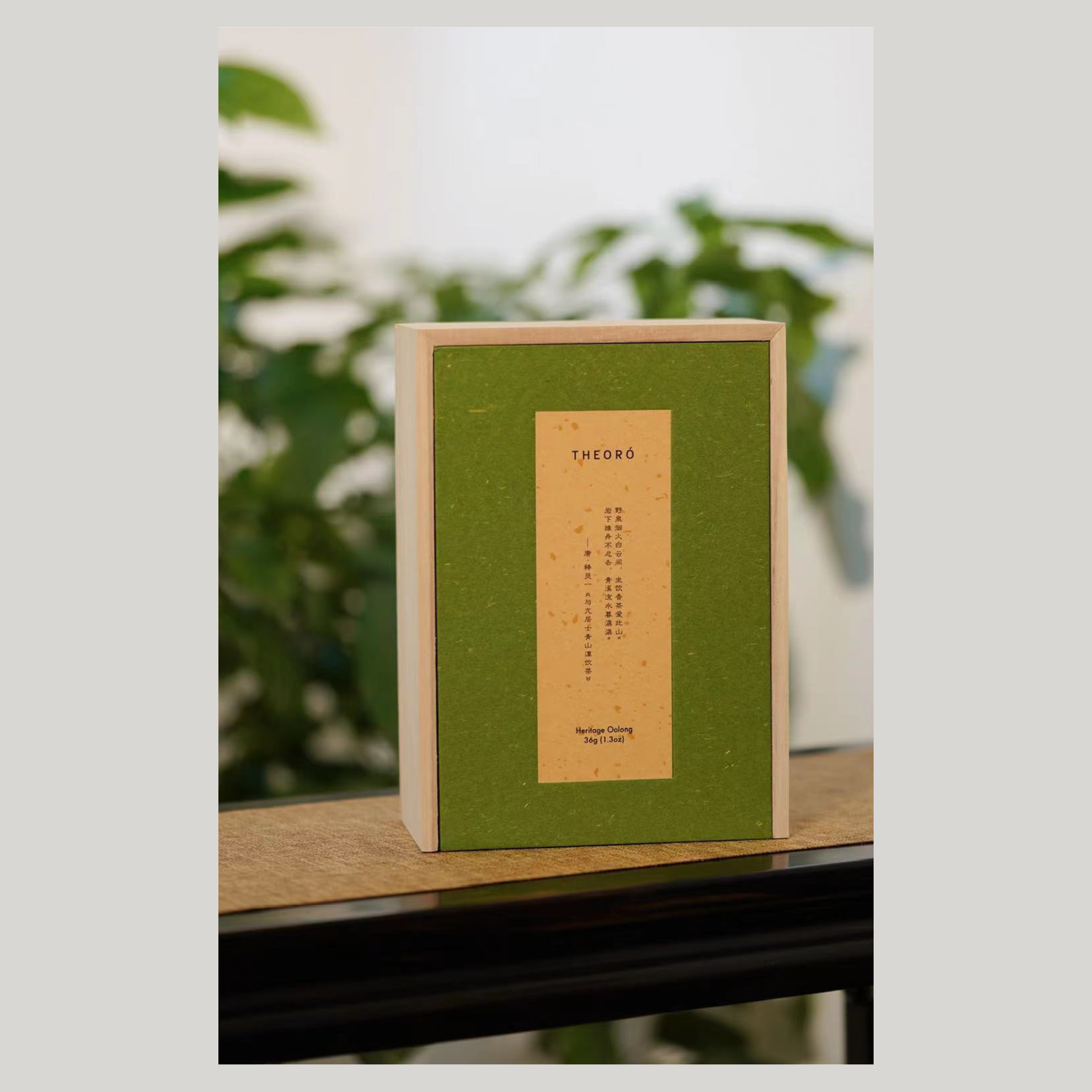

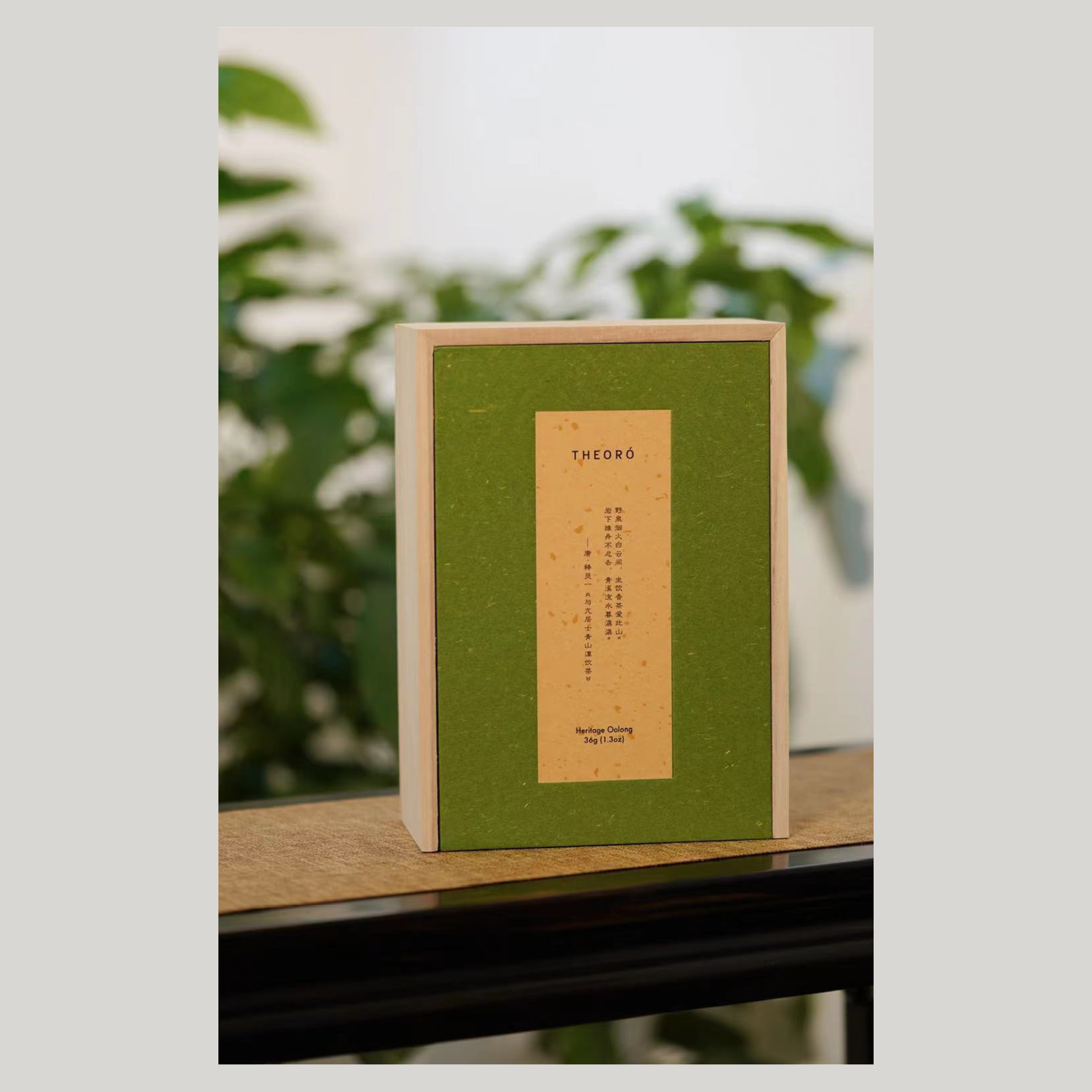

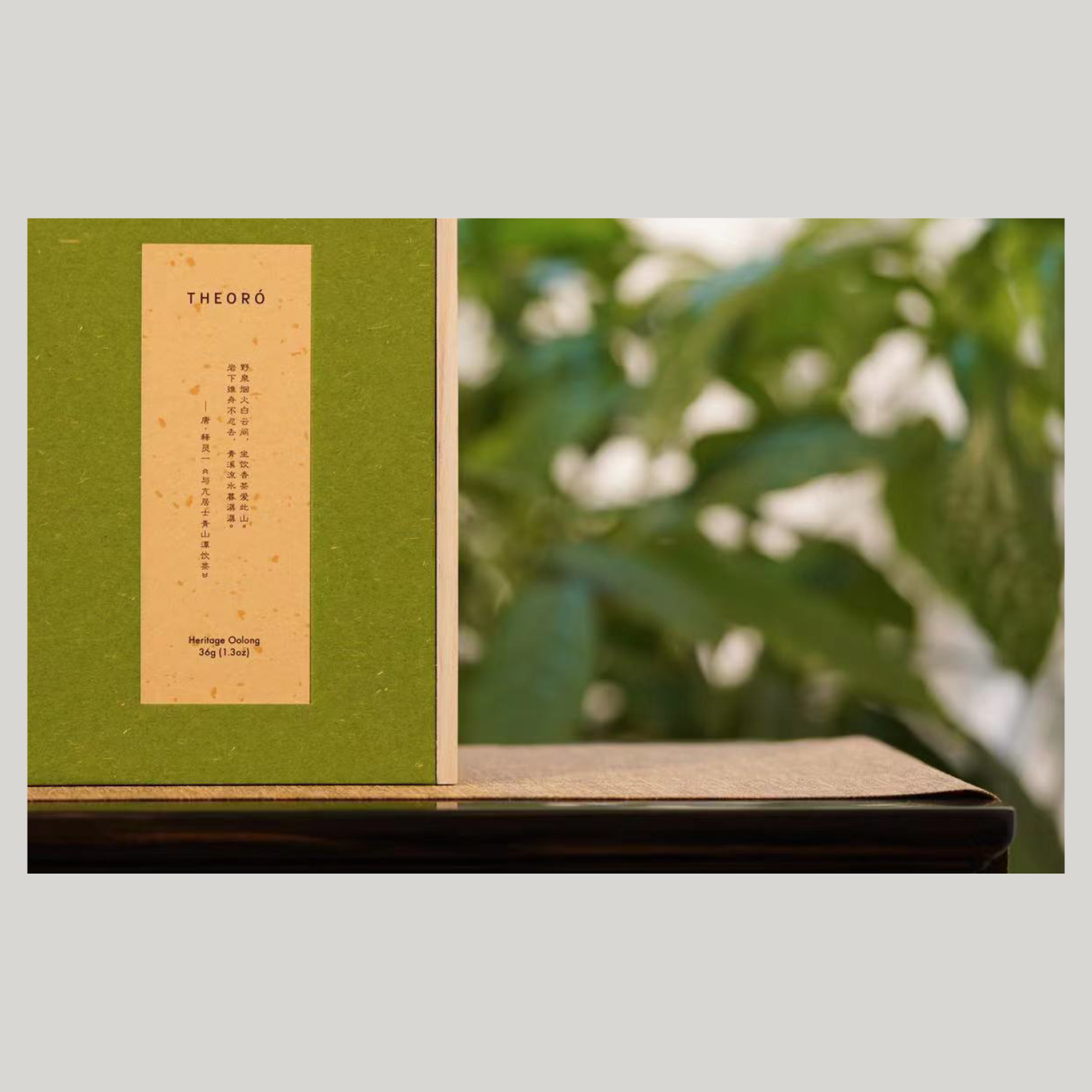

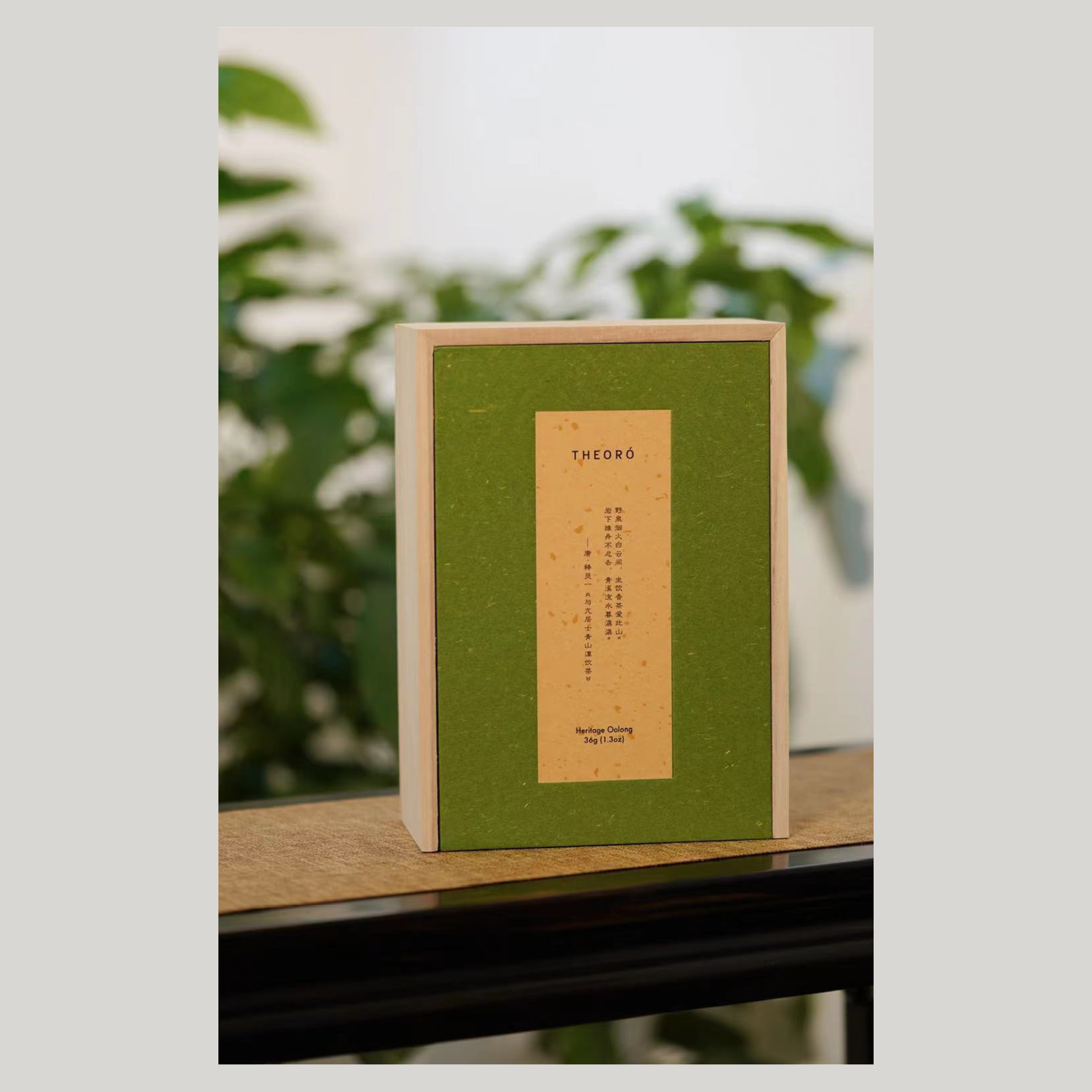

Heritage Oolong

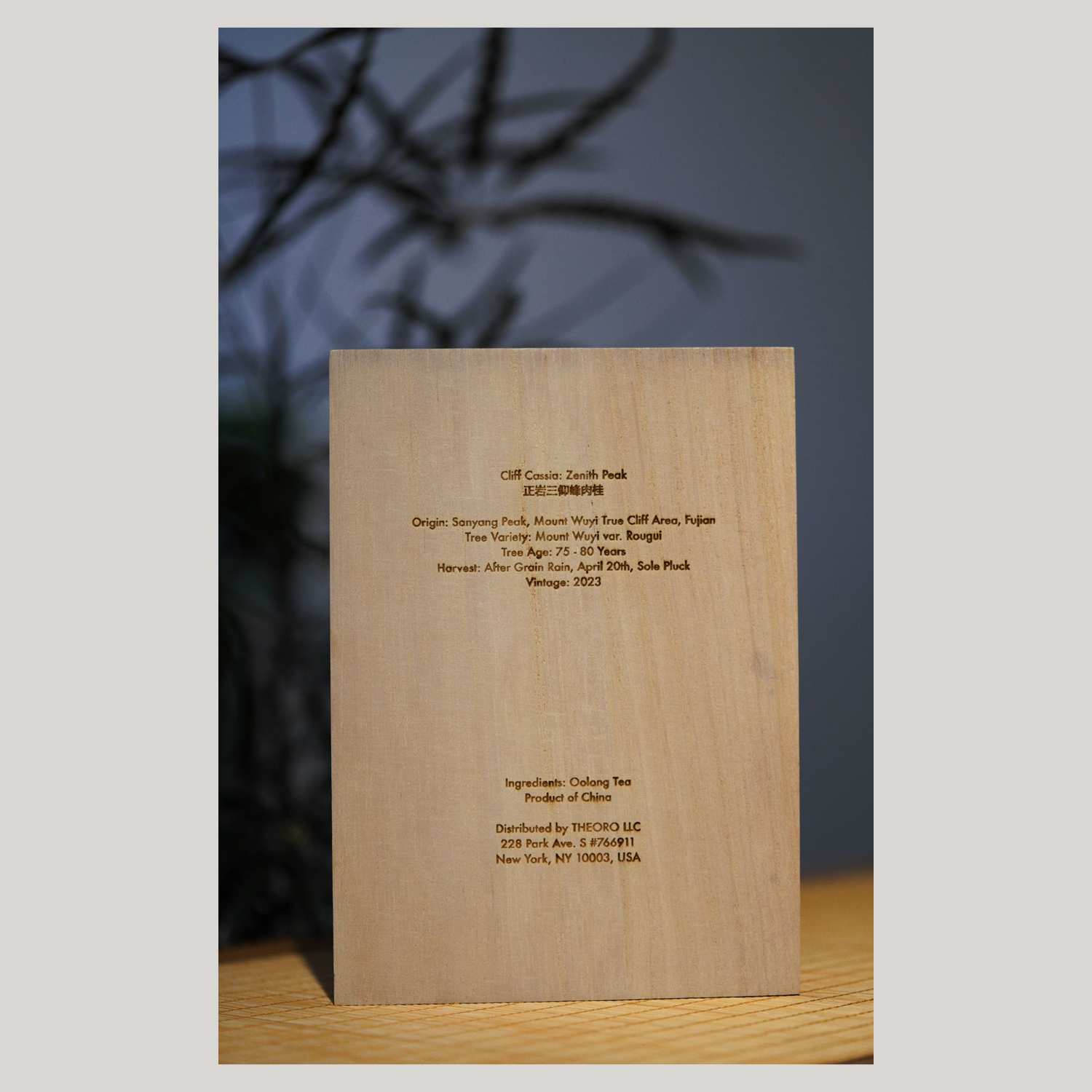

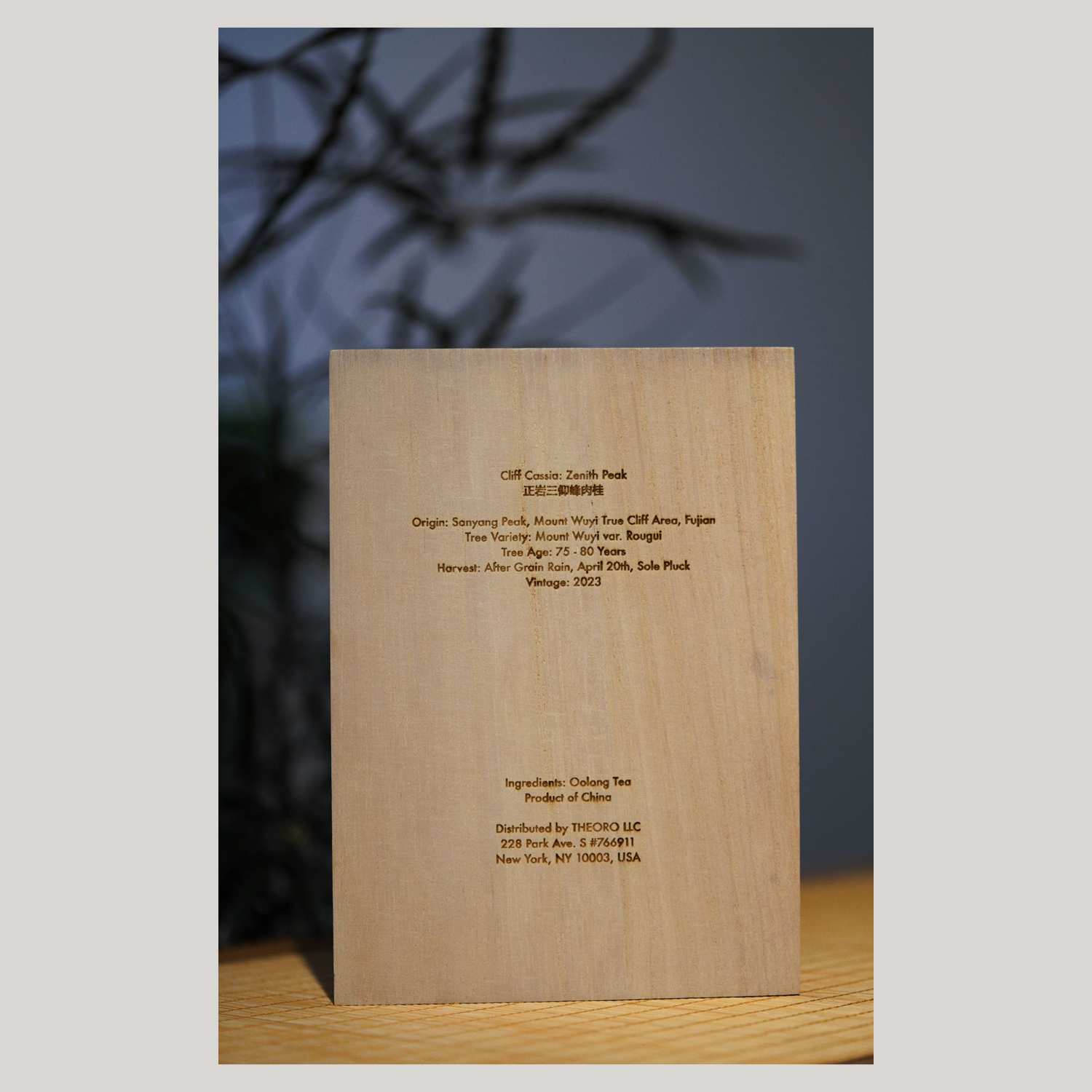

Cliff Cassia: Zenith Peak

正岩三仰峰肉桂

Origin: Fujian, Mount Wuyi True Cliff Area, Sanyang Peak

Tree Variety: Sanyang Peak Camellia Sinensis var. Rougui

Tree Age: 75 to 85 Years

Harvest: After Grain Rain, April 20th, Sole Pluck

Vintage: 2023

Each Box: 36g / 10 Packets / Makes 60+ Cups (487+ fl oz)

Each Packet: 3.6g / Makes 6+ Cups (48.7+ fl oz)

Maximum $2.49 per Cup ($4.93 per 16 fl oz)

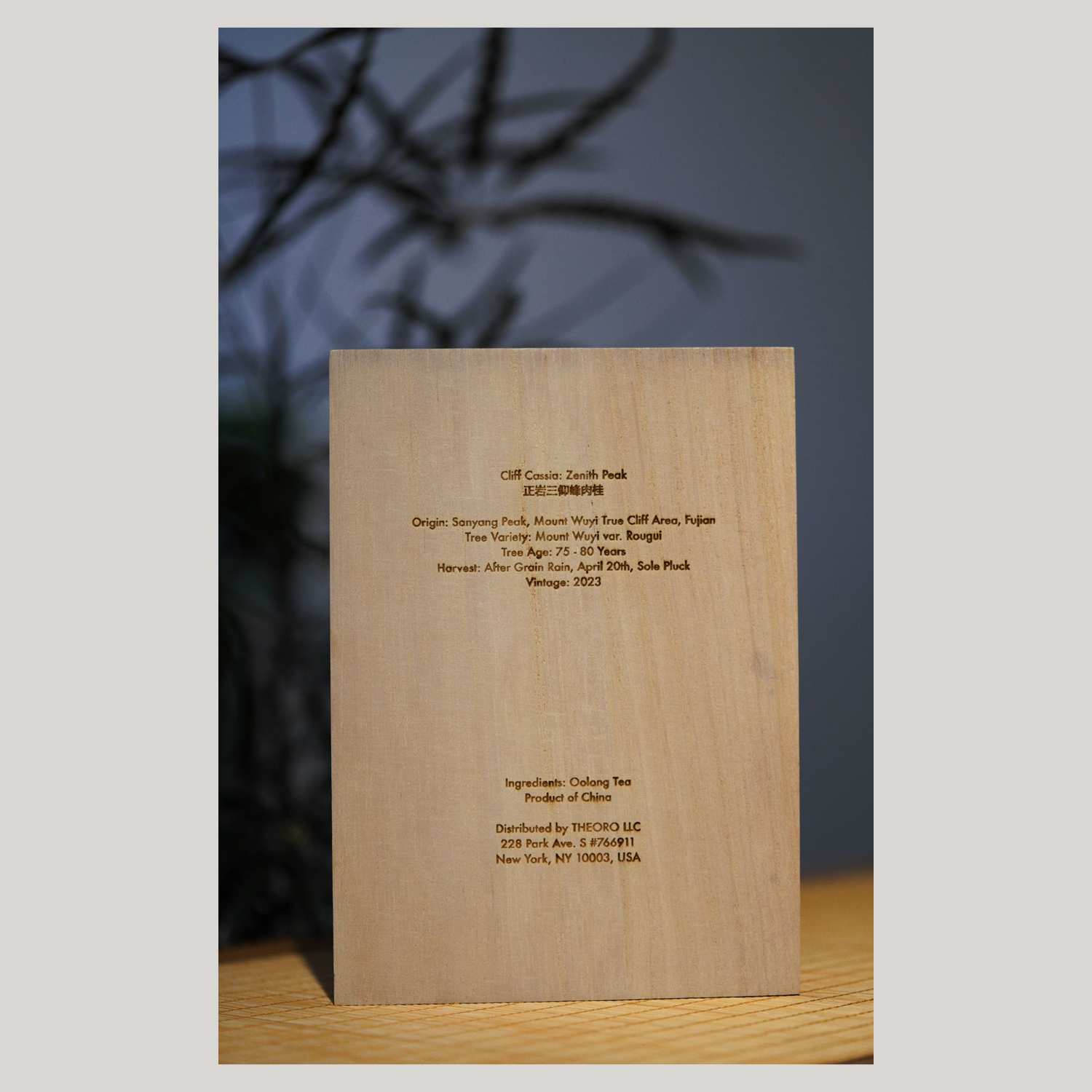

Cliff Cassia: Zenith Peak

正岩三仰峰肉桂

Origin: Fujian, Mount Wuyi True Cliff Area, Sanyang Peak

Tree Variety: Sanyang Peak Camellia Sinensis var. Rougui

Tree Age: 75 to 85 Years

Harvest: After Grain Rain, April 20th, Sole Pluck

Vintage: 2023

Each Box: 36g / 10 Packets / Makes 60+ Cups (487+ fl oz)

Each Packet: 3.6g / Makes 6+ Cups (48.7+ fl oz)

Maximum $2.49 per Cup ($4.93 per 16 fl oz)

Cliff Cassia: Zenith Peak

正岩三仰峰肉桂

Origin: Fujian, Mount Wuyi True Cliff Area, Sanyang Peak

Tree Variety: Sanyang Peak Camellia Sinensis var. Rougui

Tree Age: 75 to 85 Years

Harvest: After Grain Rain, April 20th, Sole Pluck

Vintage: 2023

Each Box: 36g / 10 Packets / Makes 60+ Cups (487+ fl oz)

Each Packet: 3.6g / Makes 6+ Cups (48.7+ fl oz)

Maximum $2.49 per Cup ($4.93 per 16 fl oz)

Profile

Aroma: Cinnamon, ginger, musk

Flavor: Scotch, black pepper, pecan, clove

Vitality: Pungent mouthfeel, robust, malty-sweet lingering

Mood: Assertive, courageous, daring, gritty

enjoyment

-

Water: Spring water or purified water.

Temperature: Approximately 212°F (100°C).

Tea-to-Water Ratio: 1 packet of tea per 1/2 cup of water for each infusion.

Tea Ware: Lidded bowl, small teapot, or water bottle with a removable filter.

-

1 ~ 6: Steep quickly, for about 5 seconds each.

> 6 steeps: Adjust steeping time according to personal preference.

-

Servings: For optimal enjoyment, use each packet for 12 infusions throughout the day.

Duration: Best enjoyed within 1 day.

When: Avoid on an empty stomach, and if you're sensitive to caffeine, skip it after dinner.

Frequency: Limit to 1 packet per day.

-

Rich food such as cheese, pizza, pasta, chicken noodle soup perfectly complements this tea. It also pairs elegantly with creamy dessert like cheesecake, mille crepe cake or western style dessert.

Legacy

Oolong tea is renowned for its strong fragrance and rich flavor. Representative tea include Wuyi Cliff Tea from northern Fujian, Anxi Iron Goddess of Mercy from southern Fujian, and Phoenix in Solitary Blossom from Guangdong. The Wuyi Mountains in northern Fujian, known for their breathtaking beauty, are regarded as the most magnificent in Southeast China. In the winding valleys and streams, where rocky cliffs and rugged terrain dominate, the robust Wuyi rock tea thrives. It is said that "every cliff has tea, and without cliffs, there is no tea," highlighting the unique relationship between the rocky landscape and the tea it produces.

Su Shi’s poem, “Wuyi Creek’s millet-sized tea, front and back guarded by Ding and Cai,” mocks the two high-ranking officials, Ding Wei and Cai Xiang, who supervised the production of imperial tribute tea in Wuyi during the Song Dynasty. This reflects how highly the imperial court valued Wuyi tea at the time. In another poem, Fan Zhongyan wrote: “The rare tea along the creek reigns supreme, planted by Wuyi immortals since ancient times.” Since ancient times, tea farmers in Wuyi have utilized the natural terrain, cultivating tea in cliff crevices and stone cracks, creating the distinctive “bonsai-like” tea gardens that we see today.

Wuyi rock tea has long been prized for its taste, with fragrance found within the flavor. Song Huizong’s “Daguan Tea Treatise” provides valuable insights for tea farmers and connoisseurs. He states, “Tea is valued for its taste above all, with smooth, sweet, and rich qualities constituting the ideal flavor, found only in the superior teas of Beiyuan.” When drinking Wuyi rock tea, if one focuses solely on aroma, it may not compare to other oolongs like Minnan Tieguanyin, Taiwan oolong, or Phoenix Dancong. In his poem “Song of Tea Competition,” Fan Zhongyan praised the tea’s taste, stating, “The taste of tea refreshes like the lightness of cream, while its fragrance is subtler than orchids or iris,” emphasizing taste over aroma.

In the Ming Dynasty, Wu Shizhi’s “Wuyi Miscellanea” described: “I tried a little Wuyi tea, processed using the method near Songpang, brewed with water from the Tiger Roaring Spring beneath Wuyi’s cliffs. Its three virtues combined perfectly, and the tea had a sweet, soft, and rocky flavor.” This “cloudy stone sweetness” might be what we refer to as the “rocky essence.” To understand the phrase “rocky essence and floral fragrance,” we may recall Su Shi’s “pure in spirit, rich in body” or Emperor Qianlong’s “clear and harmonious, with a firm backbone.” When tasting Wuyi tea, Su Shi described it as “the taste endures long after the words are gone,” while Emperor Qianlong praised it as “savoring its lingering sweetness, the pleasure grows with every sip.” Though separated by centuries, they both discovered the essence of Wuyi rock tea: its rich, broth-like tea soup, with a fragrance that clings to the throat. Its flavor is neither bitter nor astringent, known as “smooth,” and its pure, natural aroma, free of any off-flavors, is described as “true.” What left both speechless was likely the lively, vibrant quality of the tea, where each sip brought forth a new experience, rich in layers and depth.

In the Qing Dynasty, the scholar Yuan Mei, though initially partial to his local Longjing tea, once found Wuyi rock tea too bitter, likening it to drinking medicine. However, after visiting Manting Peak and tasting rock tea again, his opinion drastically changed. In his “Suiyuan Food List,” he described rock tea as follows: “One cannot bear to swallow it at once; first, one inhales its aroma, then slowly savors its taste. After a cup, the mind calms, and anxiety fades away, leaving a feeling of joy and contentment. After experiencing this, Longjing, while light and fresh, seems thin in flavor, and Yixing tea, though good, lacks depth. It’s like comparing jade to crystal; the quality is different. Wuyi tea, revered around the world, truly deserves its fame, and it can be steeped up to three times with the flavor still lingering.”

Authenticity

-

The classification of the growing regions for Wuyi rock tea began in the Qing Dynasty. In the “Continued Tea Classic,” Lu Tingcan, a county magistrate of Chong’an during the Qing Dynasty, wrote: “Wuyi tea, those grown on the mountains are rock teas, while those near water are called ‘zhou’ teas. Rock tea is superior, while ‘zhou’ tea is second. Among rock teas, those from the northern mountains are the best, followed by those from the southern mountains.”

Nowadays for Wuyi Cliff Tea, there are four major level of origin from best to least:

True Cliff Area, which represent location within the Mount Wuyi Scenic Area;

Half Cliff Area, which are Hills and semi-hilly mountainous areas nearby the Mount Wuyi Scenic Area;

None Cliff Area, which are plains and farmland nearby the Mount Wuyi Scenic Area;

Wuyi Area, which are the administrative region governed by Wuyi City

In popular misunderstanding, the "Three Pits and Two Gullies" are often considered to represent the core production area within the True Cliff Area, which the three pits refer to Niulan Pit, Huiyuan Pit, and Daoshui Pit, while the two gullies are Liuxiang Gully and Wuyuan Gully. However, the term "Three Pits and Two Gullies" is actually a broader geographical concept. It can refer specifically to these areas, but also more generally to any high-quality tea-growing region within the True Cliff Area.

For example, Sanyang Peak, located at a higher altitude, sees streams converge through Wuyuan Gully and flow into the Matou Cliff tea area. Other areas, such as Bamboo Liar, Shuilian Cave, Nine Dragons' Liar, Tianxin Cliff, Dakengkou Pit, Ghost Cave, and Top Scholar Ridge, are sometimes considered to have even better growing conditions and tea quality than the traditionally designated "Three Pits and Two Gullies" region.

Different tea tree varieties often have their own unique preferred micro-regions for optimal growth. For Camellia sinensis var. Rougui, the ideal micro-regions include: Niulan Pit, Matou Cliff, Nine Dragons' Liar, Huxiao Cliff, Tianxin Cliff, Qingshi Cliff, Sanyang Peak, and Bamboo Liar.

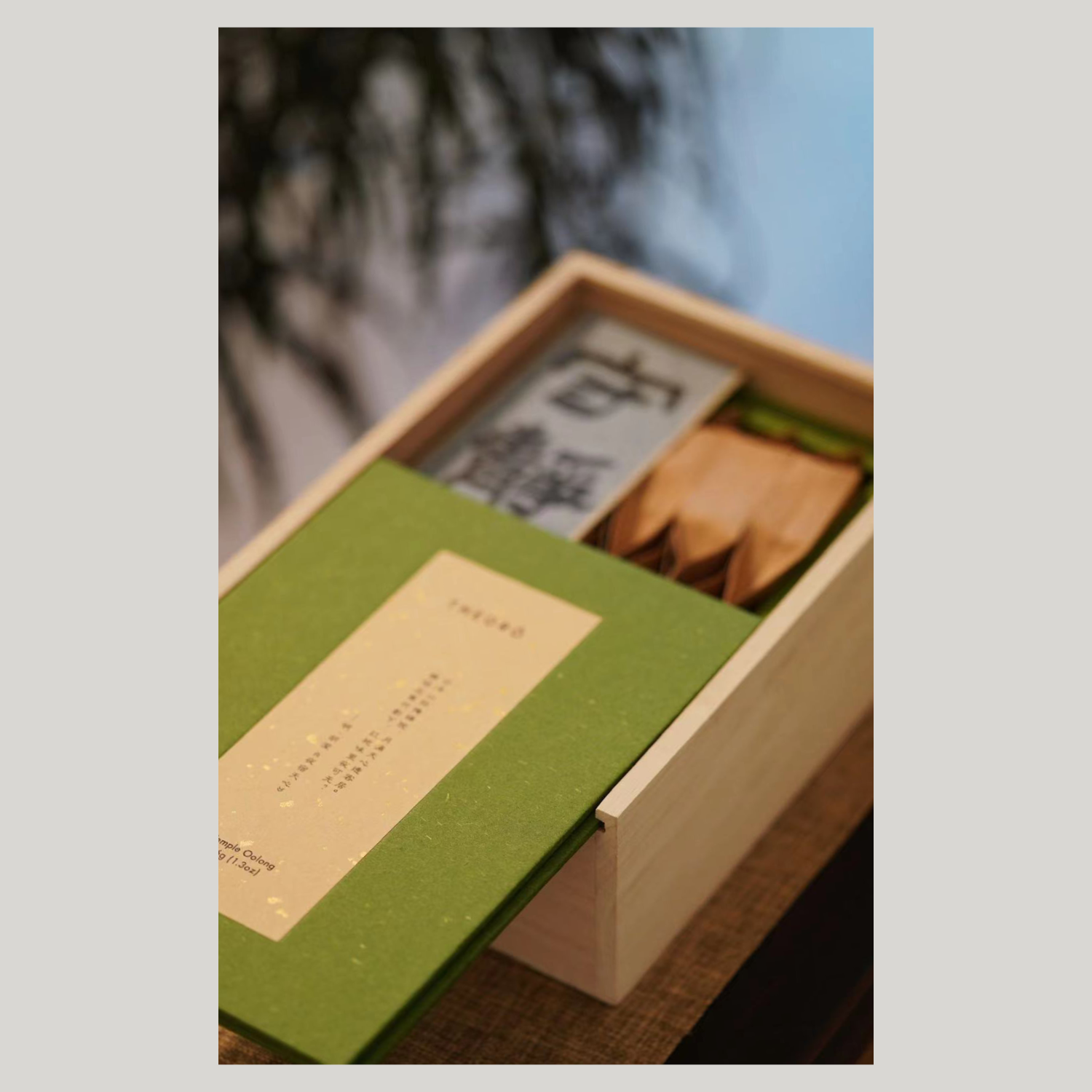

THEORÓ Heritage Oolong come from Sanyang Peak within the Mount Wuyi True Cliff Area.

-

In the world of oolong tea, mastering the complexities of Wuyi rock tea is no simple task, largely due to the sheer number and variety of its famous cultivars. According to Lin Fuquan's 1943 survey, there were as many as 280 distinguished varieties in the Wuyi Mountains alone.

Today, many of these can still be found, with some named after their growing environment, such as "No Sky" (*Bujian Tian*), "Mountain Dragon" (*Guoshanlong*), and "Water Immortal" (*Shuizhongxian*); others are named for their physical characteristics, like "Iron Arhat" (*Tie Luohan*), "Golden Turtle" (*Shui Jingui*), and "Jade Qilin" (*Yu Qilin*); and some are named for the shape of their leaves, such as "Golden Willow" (*Jin Liutiao*), "Melon Seed Gold" (*Guazi Jin*), and "Inverted Willow" (*Daoye Liu*). Certain teas are even named for their fragrance, like "Cassia" (Rougui), "Ten-Mile Fragrance" (*Shili Xiang*), and "White Osmanthus" (*Bai Ruixiang*). Others take their names from mythology or other factors, such as "Da Hong Pao," "White Cockscomb" (*Bai Jiguang*), and "Golden Turtle" (*Shui Jingui*). The list is extensive and almost endless.

The abundance of famous Wuyi Mountain tea cultivars is truly overwhelming. Each has its own distinct charm: the mellow taste of Shuixian, the spicy aroma of Rougui, the delicate fragrance of Que She, the medicinal notes of Tie Luohan, the wintersweet scent of Shui Jingui, the osmanthus fragrance of Qidan, and the sweet corn-like aroma of Bai Jiguang. Their fragrances linger endlessly in the air, with each variety showcasing its own unique beauty and qualities, competing in brilliance.

THEORÓ Heritage Oolong uses leaves from Sanyang Peak Camellia Sinensis var. Rougui.

-

THEORÓ Heritage Oolong was harvested from trees that were around 80 years old in 2023.

-

The tea leaves for oolong tea are harvested using the “open face” picking method, capturing the moment when the leaves reach peak maturity. At this stage, the new shoots have a high level of carotene, lower catechin content, and higher reducing sugars, providing the foundational substances for the tea’s rich aroma and mellow flavor.

THEORÓ Heritage Oolong is harvested only once a year, specifically during the spring season, on the day of Grain Rain, April 20th.

-

THEORÓ Heritage Oolong is from the year 2023.

Craftsmanship

-

The withering process is when the fresh, firm leaves lose moisture, and become soft and limp after being sun-dried, and it must be done just right. If too much water is lost, the leaves become “dead leaves,” but if insufficient moisture is released, it affects the next stage of processing.

In short, “flipping the leaves without damaging them” is the key, proper technique is essential, and judging the right timing and controlling the degree of withering are the soul of the process.

-

The sculpting of Wuyi Cliff Tea involves mainly shaking the tea leaves. This is the key process that determines the quality of Cliff Tea, and it also requires the highest level of skill.

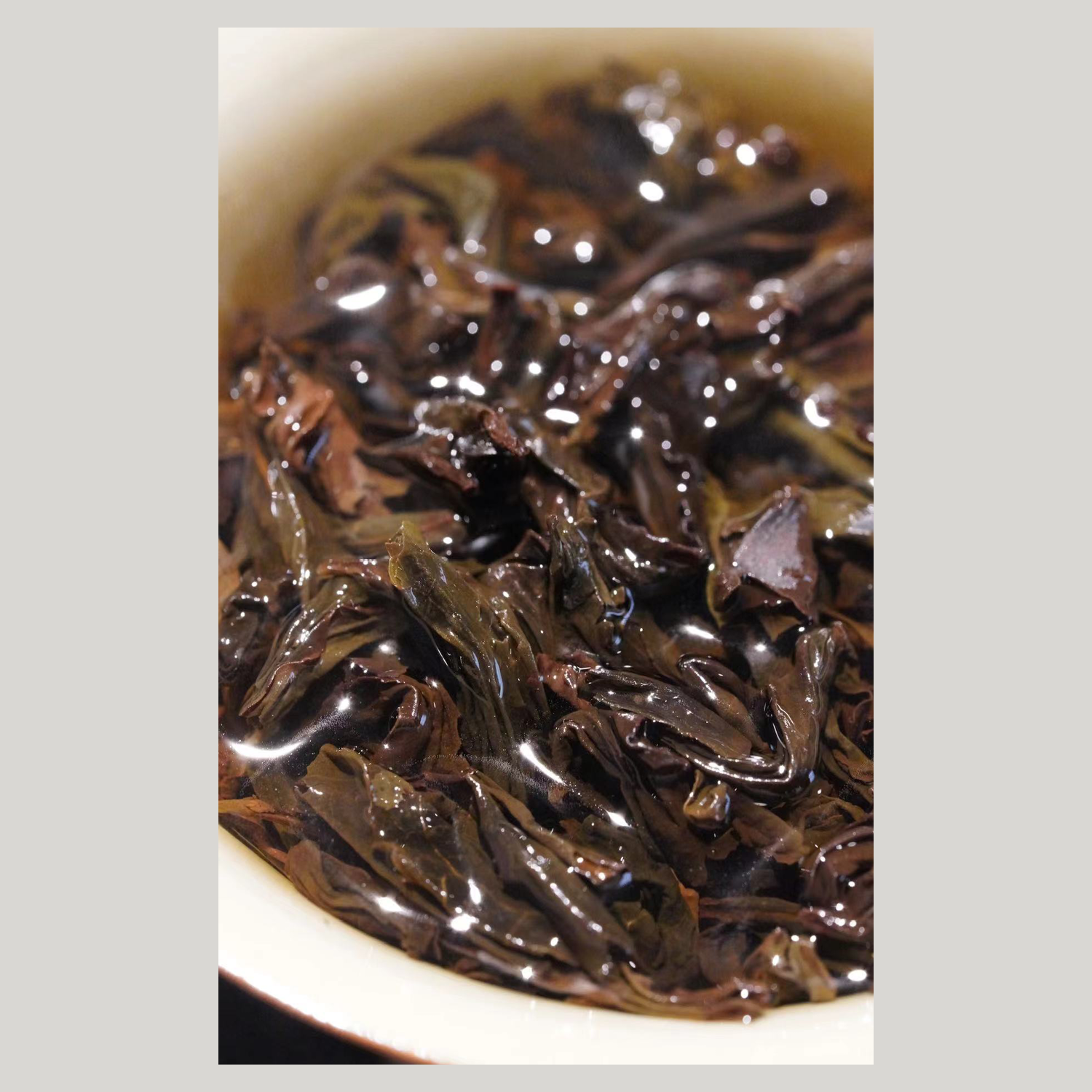

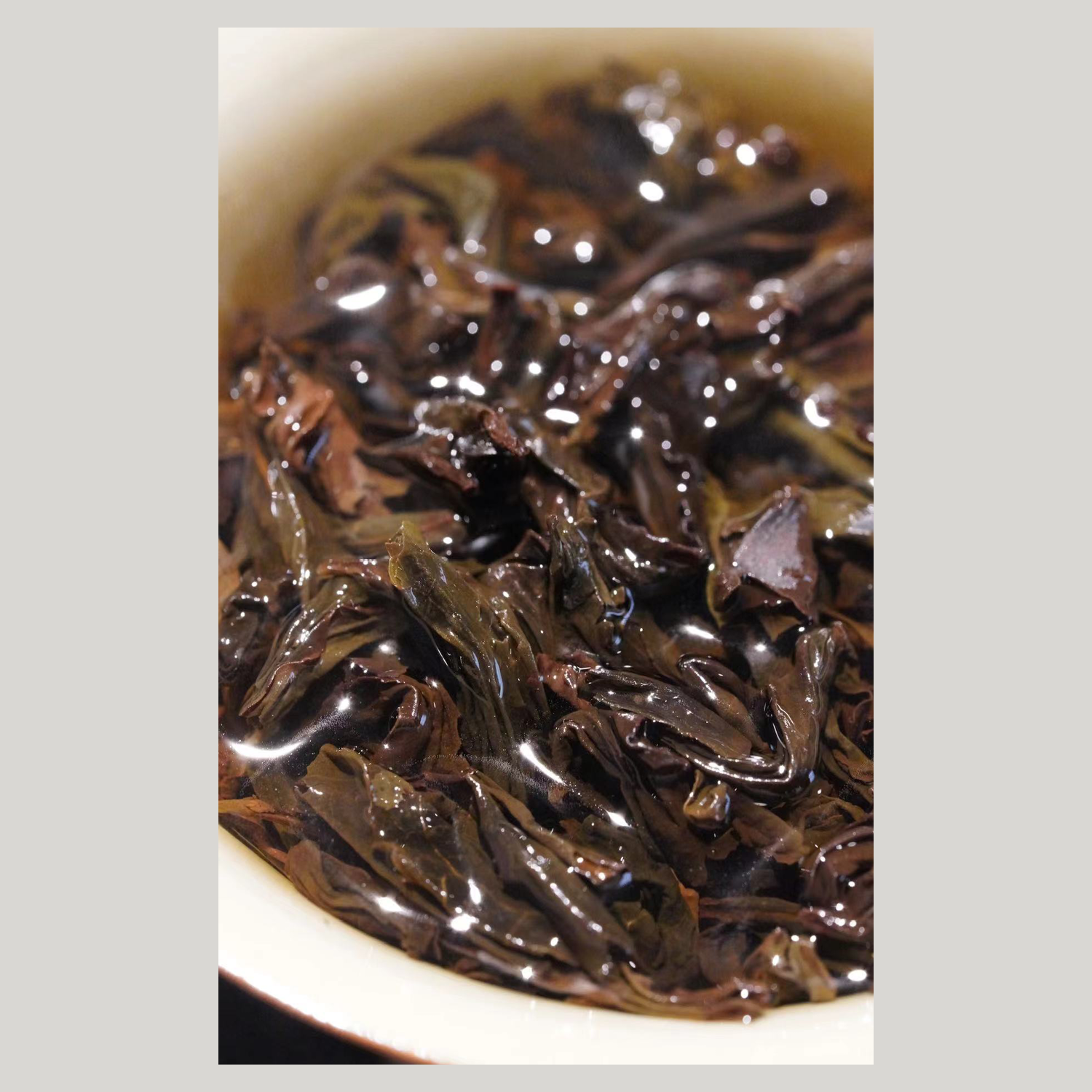

It involves alternating between shaking and resting to encourage the edges of the leaves to rub and collide, releasing moisture and triggering hydrolysis and oxidation of the internal compounds. This continues until the leaf edges are broken, creating a characteristic “green leaves with red borders.” When the green aroma transforms into a fresh fragrance, and the leaf color changes to yellow-green with a turtle-shell shape on the surface (commonly called “spoon leaves”), it indicates that the shaking process is complete.

The phrases "observe the leaves to make the tea" refer to the process of moisture loss and oxidation happening simultaneously. Controlling the extent of moisture loss and the rhythm of oxidation is crucial to producing a good tea. Whether looking at the variety, the thickness, size, or firmness of the leaves, what is ultimately being observed is the water. As moisture evaporates, different aromas emerge, and subtle changes occur in the leaves, such as softening, color turning from green to red, the sound of the shaking becoming muffled, and changes in the shape and texture of the leaves.

As long as the "three reds and seven greens" color pattern and the "spoon shape" are achieved during the normal process, the desired qualities will naturally develop in the tea.

-

The fixation of Cliff Tea involves mainly pan-roasting. This technique uses high temperatures to stop oxidation and stabilize the quality of the tea. At the same time, the high temperature helps further eliminate the low-boiling-point grassy odors from the original aromatic components, allowing the higher-boiling-point floral and fruity aromas to become more prominent. Under these heat conditions, new aromatic compounds may also form.

-

After completing the fixation process, the tea leaves are removed from the pan while still hot and shaped into strips. During the rolling process, the tea juice is squeezed out and coats the surface of the leaves, promoting the mixture and interaction of the internal substances and facilitating some degree of transformation. This process enhances the richness of the tea liquor.

-

A high-temperature roasting method is used to quickly remove moisture from the tea leaves until 60-70% dry. Visible open fire may be used, but without direct flames.

The roasting process further inhibits enzymatic oxidation, evaporates moisture, and reduces bitterness. The practice of roasting rock tea dates back to at least the Ming Dynasty. The Compendium of Materia Medica provides an intriguing reference: “Recently, the practice of Fujian tea roasting has become well-established. Only those from northern Jianzhou, whose character differs from others, are suitable for imperial tribute. Sun-dried and roasted, the more they are exposed to fire, the better they become. However, if they see too much fire, they harden and cannot be stored long, their color and taste deteriorating.” This reflects Wuyi rock tea’s distinctive quality, where sun-drying combined with light roasting enhances flavor.

-

After the initial roasting, the tea becomes “rough tea” (Maocha), which still has a coarse aroma. This marks the first important step, but further sorting and refinement are needed. The tea maker removes the stems the next morning.

-

The final roasting (re-roasting) is the crucial step that defines the quality of true rock tea. Traditional roasting for rock tea typically occurs after the “White Dew” solar term in autumn when the weather is cooler and the air humidity is lower, which is ideal for the gradual drying and roasting process. The Qing Dynasty tea master Liang Zhangju once said, “The roasting method of Wuyi tea is unmatched in the world.” This statement holds true. The final roasting enhances the tea’s aroma and flavor, encouraging the transformation of the internal compounds and giving the tea a rich, mellow taste.

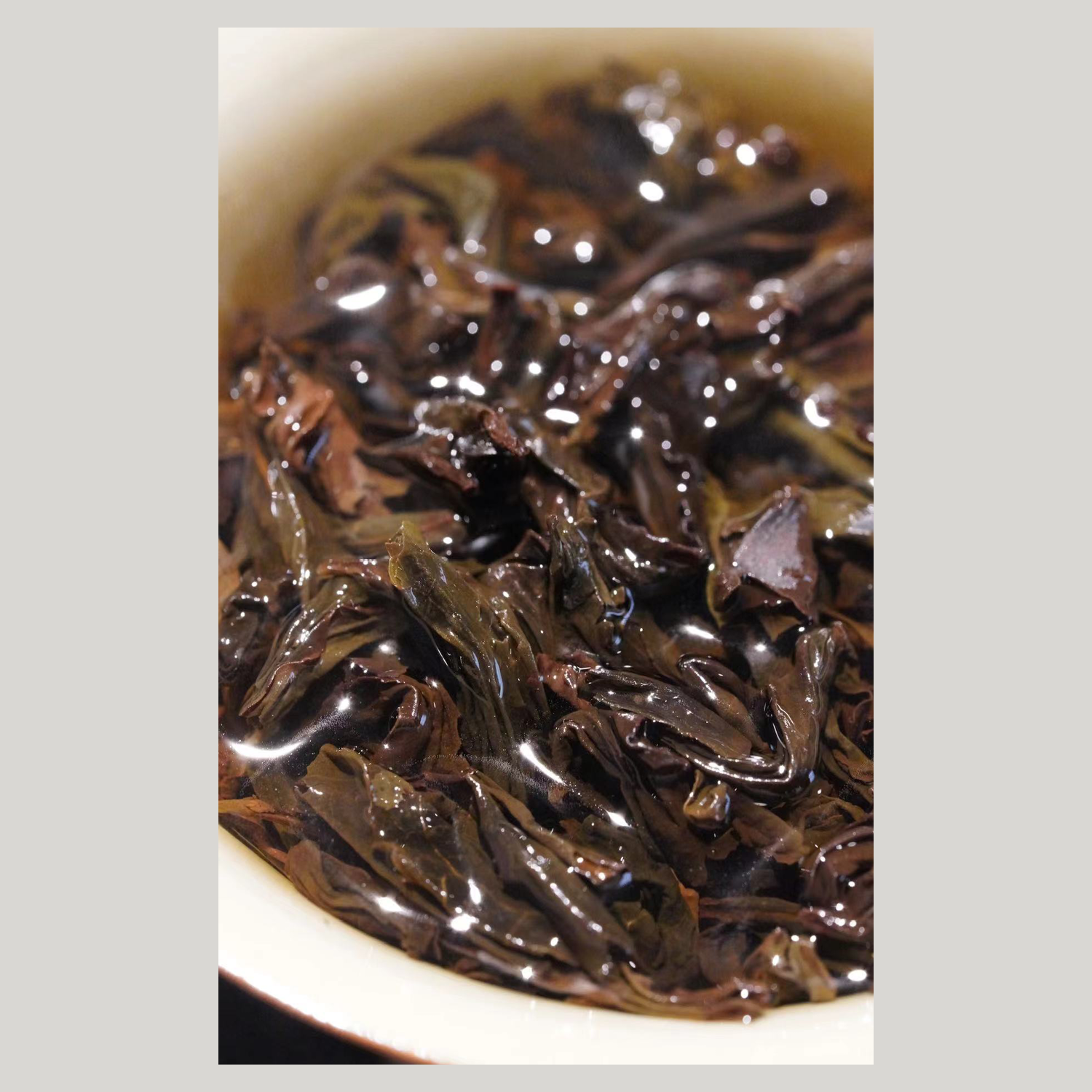

The higher the grade of rock tea, the more it requires low-temperature, slow roasting. A well-crafted traditional Wuyi rock tea should have a combination of rich caramel and floral-fruity aromas, with glossy leaves that shine with an oily luster. The tea should have a robust aroma without any burnt or overly roasted smell, a smooth and thick texture, bright and clear tea liquor, and a refreshing fragrance that lingers in the throat. The tea should also have a high steeping endurance, with the final brews still holding up well without bitterness or astringency. The bottom leaves should exhibit the characteristic “toad’s back” pattern, showing they have been fully roasted.